Tariffs

Good or Bad?

Since President Trump took office as our 47th president, it seems a single day doesn’t go by without him uttering his favorite word: tariffs.

Much has been said on this topic, yet at the same time, I feel like nothing of substance has actually been said.

The Trump administration indicates tariffs be good for America, and will return us to a place of trade reciprocity.

Detractors are quick to point out that tariffs will create an inflationary environment, and will make US companies less competitive as we give them a leg up in the global market.

So which is it?

Early Adoption and Alexander Hamilton’s Vision

The U.S. tariff system originated with the Tariff Act of 1789, signed by President George Washington as the second legislative act of the new republic.

Designed to address the federal government’s urgent need for revenue and to protect nascent industries, this law imposed an average duty of 5% on imports, with higher rates for manufactured goods like steel and textiles.

Alexander Hamilton, yes the same guy from the musical, championed tariffs as a dual-purpose mechanism: to fund national debt repayment and to shield “infant industries” from foreign competition.

In his “Report on Manufactures” (1791), Hamilton argued that economic independence was inseparable from political sovereignty, advocating for targeted protectionism to spur domestic manufacturing.

The early tariff regime faced practical challenges. Between 1792 and 1816, Congress passed 25 tariff acts adjusting rates in response to fiscal needs and trade imbalances.

The War of 1812 marked a turning point. As British blockades disrupted imports, they inadvertently boosted U.S. manufacturing.

Postwar tariffs surged to an average of 35% by 1816, driven by industrialists in the Northeast seeking to preserve their wartime gains.

By 1820, average rates reached 40%, cementing tariffs as the federal government’s primary revenue source, accounting for 80–95% of its income until the Civil War in 1861.

Tariffs and Sectional Tensions

The protective tariff system exacerbated regional divides in the 19th century and became a latent cause of the Civil War.

Northern manufacturers benefited from reduced competition, while Southern agrarian states, reliant on imported goods and export-oriented crops like cotton, bore the brunt of the higher prices.

The 1828 “Tariff of Abominations,” which raised rates to an average of 25%, ignited the Nullification Crisis as South Carolina threatened secession over perceived economic exploitation.

Though the crisis was defused by a compromise lowering rates, tensions persisted, foreshadowing the broader sectional conflict over states’ rights and economic policy.

Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, South Carolina succeeded from the Union, citing several reasons in its Declaration of Secession on December 24, 1860.

The state emphasized that Northern states were violating the Fugitive Slave Act by refusing to return escaped slaves, and Abraham Lincoln, a Republican opposed to slavery’s expansion, was seen as an existential threat to their way of life and economic interests.

South Carolina also pointed to the increasing hostility of non-slaveholding states toward slavery, and framed its decision as an issue of states' rights, arguing that the Constitution was a compact between sovereign states that could be dissolved if violated.

Economic concerns, including federal tariffs, further fueled secession, as the state’s cotton-based economy was deeply reliant on slave labor and low cost imported goods.

These factors reinforced South Carolina’s decision to leave the Union, with its secession document making clear that slavery was the central issue at stake.

The Three R’s: Revenue, Restriction, and Reciprocity

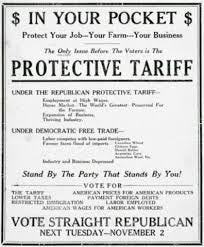

Following the Civil War, President William McKinley, a Republican from Ohio, initially championed protectionism as a congressman, architecting the 1890 McKinley Tariff.

This law elevated average rates to 48%, targeting industries like tin plate, woolens, and ceramics to spur domestic production. The strategy succeeded in the short term: U.S. tin plate output surged from 0 to 120,000 tons annually within a decade, displacing British imports.

However, McKinley’s views evolved during his presidency (1897–1901). Facing budget surpluses and pressure from export-oriented industries, he pivoted toward reciprocity agreements, negotiating bilateral tariff reductions to open foreign markets.

In his 1901 speech at the Pan-American Exposition, McKinley declared, “The period of exclusiveness is past,” advocating for tariffs as leverage to secure fair trade terms rather than outright barriers. This shift reflected a pragmatic recognition that excessive protectionism could stifle export growth and diplomatic relations.

President McKinley was assassinated on September 6, 1901, by Leon F. Czolgosz, an anarchist who opposed all forms of government, rulers, and institutions like voting, religion, and marriage.

Czolgosz viewed McKinley as a symbol of the oppressive system he despised and believed the President was an "enemy of the people" whose policies failed to support the working class.

In his confession, he expressed frustration that McKinley promoted national prosperity while ordinary workers saw no real economic benefit. His actions were part of a broader global wave of anarchist violence, during which several world leaders were assassinated.

The attack occurred at a public reception at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, where McKinley was easily accessible. Despite widespread speculation, Czolgosz acted alone and was executed on October 29, 1901, for the assassination.

Fiscal Pressures and the 16th Amendment

By the early 20th century, tariffs faced diminishing returns as globalization reduced their efficacy as a revenue tool.

The federal government increasingly relied on excise taxes and, after 1913, income taxes following ratification of the 16th Amendment.

This shift was driven by Progressives seeking a fairer tax system and industrialists wanting lower input costs.

By 1920, income taxes surpassed tariffs as the largest revenue source, enabling tariff reductions to 15–20% under Democratic administrations.

So What?

Okay, history corner is over. What’s the verdict.

Historical data consistently demonstrates that tariffs raise consumer prices and restrict supply.

The Tax Foundation’s analysis of U.S. trade policy notes that tariffs function as regressive taxes, disproportionately affecting lower-income households by increasing the cost of essential goods.

For example, the McKinley Tariff of 1890 elevated tin plate prices by over 30%, shielding domestic producers but straining consumers and downstream industries reliant on affordable materials.

Similarly, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, which raised rates on 20,000 imported items, exacerbated the Great Depression by triggering retaliatory measures and reducing global trade volumes by 66%.

Essentially, they are good for Wall Street, but bad for Main Street.

Tariffs distort market incentives by encouraging overinvestment in protected sectors.

During the 19th century, high tariffs on textiles and machinery spurred rapid industrialization in the Northeast but created inefficiencies.

For example, many firms that flourished during wartime trade disruptions failed once normal competition resumed, revealing the fragility of artificially sustained industries.

Inflation and Middle-Class Erosion

The correlation between income tax adoption and inflation is indirect but significant.

Income taxes provided stable revenue, allowing tariffs to decline and consumer prices to fall. However, the mid-20th century saw inflation surge due to unrelated factors: wartime spending (1940s), oil shocks (1970s), and monetary policy shifts.

Middle-class stagnation since the 1970s stems more from wage suppression, automation, and declining unionization than tax structure changes, though critics argue that income taxes, combined with payroll taxes, place undue burdens on wage earners that could otherwise be solved by a tariff system.

Revenue Potential and Trade-Offs

Eliminating income taxes would require tripling tariff rates to approximately 45% across all imports, a level last seen in the 1930s.

Such a move would risk severe inflationary shocks, as seen historically, while provoking retaliatory tariffs. For example, the European Union’s 2018 countermeasures against U.S. steel tariffs targeted politically sensitive exports like bourbon and motorcycles, harming U.S. producers.

Proponents argue that reducing “wasteful spending” could offset revenue losses, but even eliminating all discretionary spending ($1.7 trillion in 2025) would cover only 40% of income tax revenue. Tariffs would still need to generate $2.5 trillion annually, a 300% increase from 2025 levels, likely collapsing import volumes and sparking an inflation.

The Art of the Deal

Here is my take. Tariffs in general are inflationary and unhelpful tools in a global economy, since they act as subsidies for companies and allow to them operate in a less competitive manner.

DeepSeek vs Meta Llama is a recent example. Because Meta had all the money in the world, DeepSeek was able to create a better open source product because constraints drove innovation.

By subsidizing US companies, we would inadvertently gimp them. Like an overprotective parent who does everything for their child, only for them to be severely disadvantaged when they have to set out on their own.

Allowing companies to lag behind competitors, US firms would eventually fail, similar to the firms that failed in the 19th century when regular, competitive market conditions returned following the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812.

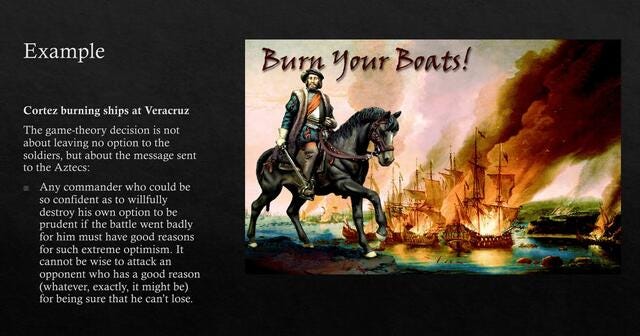

But the threat of tariffs can be extremely useful tools.

In his 1901 speech at the Pan-American Exposition, McKinley declared, “The period of exclusiveness is past,” advocating for tariffs as leverage to secure fair trade terms rather than outright barriers. This shift reflected a pragmatic recognition that excessive protectionism could stifle export growth and diplomatic relations.

Trump’s Executive Orders as Economic Leverage

On February 1, 2025, Trump signed three executive orders authorizing tariffs of 25% on most Canadian and Mexican imports and 10% on Chinese goods, invoking the Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977.

The tariffs targeted $155 billion in Canadian exports, including steel, aluminum, and energy products, while Mexico faced blanket coverage of its $538 billion in annual exports to the U.S.

Crucially, the orders included a 30-day suspension for Canada and Mexico to negotiate concessions, creating a countdown clock that amplified pressure on both governments

Faced with the prospect of 25% tariffs on 84% of its exports to the U.S., Canada announced immediate countermeasures on February 2, imposing 25% duties on $30 billion worth of American goods, including beverages, cosmetics, and paper products.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau framed the retaliation as a defense of Canadian sovereignty, urging citizens to boycott U.S. products and avoid cross-border travel.

However, behind the scenes, Ottawa recognized the existential threat posed by the tariffs: 75% of Canadian exports are destined for the U.S., and integrated supply chains in sectors like automotive manufacturing (which supports 500,000 Canadian jobs) faced imminent collapse.

By February 4, just four days later, Canada pivoted to concessions, agreeing to appoint a national “fentanyl czar” to coordinate anti-trafficking efforts and designate Mexican drug cartels as terrorist entities under the Criminal Code.

The Trudeau government’s rapid acquiescence reflected the disproportionate leverage held by the U.S.

A 50% tariff on steel and aluminum, when combined with existing duties, would have rendered Canadian metals uncompetitive in the U.S. market, threatening 45,000 jobs in Ontario and Quebec.

Mexico’s capitulation stemmed from a similar acute exposure to U.S. market dynamics.

With 81% of Mexican exports ($538 billion in 2024) reliant on U.S. consumers, tariffs would have devastated key industries:

Automotive Sector: 72% of Mexico’s $145 billion in auto exports go to the U.S., supporting 1.2 million direct jobs.

Agriculture: A 25% tariff on $47 billion in agricultural exports (avocados, tomatoes, berries) would have bankrupted 300,000 smallholder farmers.

Manufacturing: The maquiladora export-processing zones, which employ 3.4 million workers, depend on tariff-free access under USMCA rules

President Claudia Sheinbaum announced the deployment of 10,000 National Guard troops to the northern Mexican border on February 3, (two days after the EO) pledging to “seal our frontier against fentanyl and human smuggling”.

The tariff announcements triggered immediate volatility:

Currency Markets: The Canadian dollar fell 3.2% against the USD on February 1–3, while the Mexican peso depreciated by 4.7%, its steepest decline since 2020.

Equities: S&P 500 firms with >20% North American revenue exposure (e.g., Ford, General Motors) saw $45 billion in market capitalization erased on February 3.

Commodities: U.S. Midwest hot-rolled coil steel prices surged 18% to $1,150/ton, anticipating Canadian supply shortages.

Trump’s “Bazooka Diplomacy” and Asymmetric Bargaining

The events underscore Trump’s ability to utilize what economists term “bazooka diplomacy”, the deployment of overwhelming economic threats to compel concessions.

By targeting 25% of Canada’s GDP and 41% of Mexico’s GDP through tariffs, Trump exploited the lopsided interdependence in USMCA: while the U.S. accounts for 18% of Canada’s GDP via trade, Canada represents just 1.3% of U.S. GDP.

This asymmetry allowed Trump to credibly threaten disproportionate harm, knowing Ottawa and Mexico City lacked comparable retaliatory tools.

In this way, tariffs can be an incredibly effective tool to get what one wants and, in my opinion, will be how they would be deployed in the coming administration.

Let me know what you think in the comments.

Great deep dive. Thanks for taking the time to write this.

Great piece and yes the orange man does know what he is doing. Developing a piece of real estate in NYC requires negotiation with a slew of criminals and politicians (maybe really one and the same). He knows the “others” have more to lose than the US. The poker hand is delt, and the others look at the cards and fold. In the long run it will be good for the average consumer. The problem will be, those in the US that are harmed, yield a lot of political and economic power. Can it be sustained?